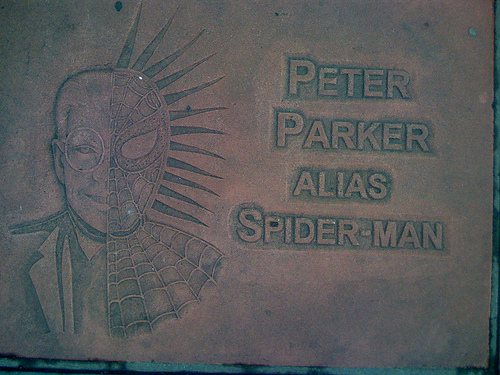

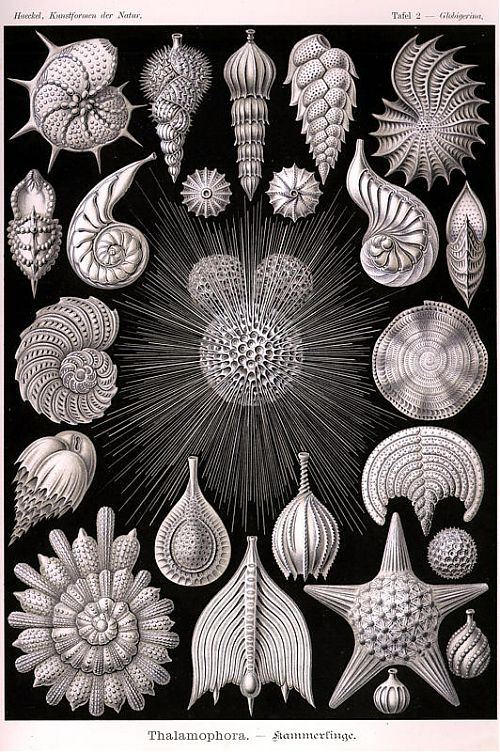

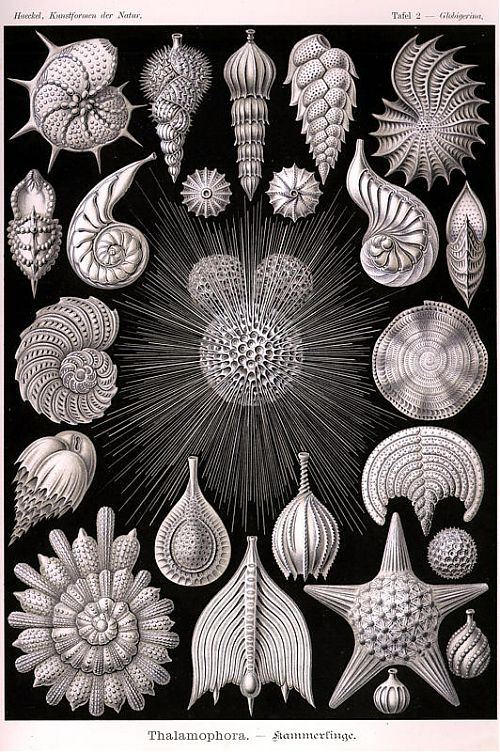

One of Ernst Haeckel’s naturalist illustrations, 1899-1904.

I fell into a bit of a well of naturalism and anatomy links, and ended up wanting to read Stuffed Animals and Pickled Heads: The Culture and Evolution of Natural History Museums, although I’m pretty sure it isn’t as critical or curious as I want it to be. One review quotes this tedious oversimplification as a “philosophical insight into the scientific and human impulse to categorize.”

“To have a concept… is to have its negation already in tow…. There is a class of things called ‘dog,’ and there is a class of things (quite substantial, in fact) that are ‘not-dog.’… Language and thought cannot really function without this most basic tool for carving up reality.”

Never heard of fuzzy continuums and the rewards of using them, I guess? Odd, since natural history museums are full of ambiguous specimens (two headed mutant dog, alleged dog-cow hybrid, newly discovered tentative dog, etc) that illustrate quite nicely the space between dog and not-dog. Sort of dog. Possible dog. Both dog and yet not dog. Natural history museums are pretty much ground zero for failed categorization schemes and fuzzy margins, sets that are more complicated than somebody was hoping they would be. Maybe the quote is just out of context. There are a lot of ellipses in there.

To balance out the sad saga of binary categories in science, I like to think about primary colours. These seem like a life-affirming, pro-ambiguity, scientific success. Primary colours are sets of colours that are chosen to maximize the usefulness of the spectrum between them. A noble, everybody-wins way to think about categorization, and also an easily visualized example of information organized into multiple overlapping continua. Wikipedia points out that “Any choice of primary colors is essentially arbitrary; for example, an early color photographic process, autochrome, typically used orange, green, and violet primaries.” Concrete! Maybe this is because colour science is so bluntly tied up in perception and perspective. It has to be aware of observer bias and intention, because it is about observing. My favourite bit of that Wikipedia page:

If a human and an animal both look at a natural color, they see it as natural; however, if both look at a color reproduced via primary colors, for example on a color television screen, the human may see it as matching the natural color, while the animal does not; in this sense, reproduction of color via primaries must be “tuned” to the color vision system of the observer.

I wonder how long it will be before someone makes a TV for dogs, with two kinds of pixels instead of RGB. Or TV for bees, with four kinds.