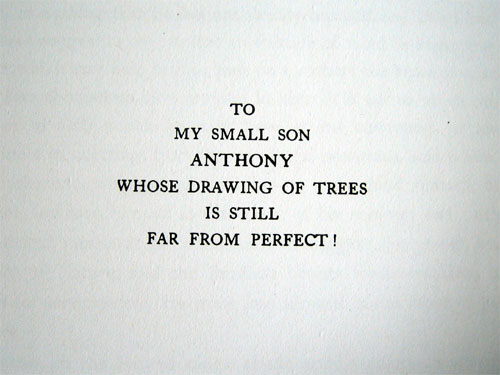

This is a bit flaky, but I’d like to propose that we are living in The Age of Complexity. Not the information age, or the age of media, internet, connectivity or whatever, but the age of complexity. I think that’s the primary obstacle in modern problems and stresses: how to stop clinging to simplified half-truths and start understanding complex, interconnected systems. Naming the thing might help us to remember to figure it out.

Complexity— and how counter-intuitive everybody seems to find it— comes up everywhere these days: in media and internet, software design, urban planning, health, environmentalism, psychology, and anything that tries to organize a group of people. I think George Lakoff’s work with the Rockridge Institute, to provide priorities and frames for progressive ideas, is part of dealing with complexity, even though his books are about politics and linguistics, not systems theory.

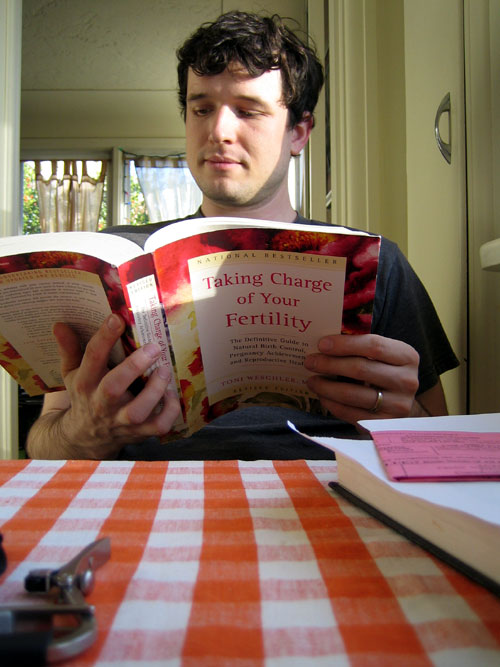

I’ve been thinking about generalism and distributed knowledge for my independent education project, too, which just struck me as a sort of complex system of learning. Rather than specializing in a particular field, I’m trying to figure out what would count as graduate level work on a general problem (the topic so far is what I want my death to be like). And rather than hook up with a structure or institution, I’m trying to use a lot of small, independent resources. This pleases me more and more, because it suits how I think about information and the web, etc. (Is that called symmetry, when different levels or parts of a system have the same patterns?)

So. This is the link that finally put me over the edge, when I was catching up on Kottke today.

I wanted to ask a more general question: how can people stop needing simple stories, and what can we use instead? I remember, back when I first started making websites in the ’90s, when I first understood hypertext as an alternative to linear narrative, it seemed like the same idea that Kottke is looking at, up there, in the history of science. (How’s that for a hyper sentence, remembering things in the past and present? It seems accurate so I’m going to leave it.) My favourite websites are still the ones that use links as complex context, instead of in sequence.

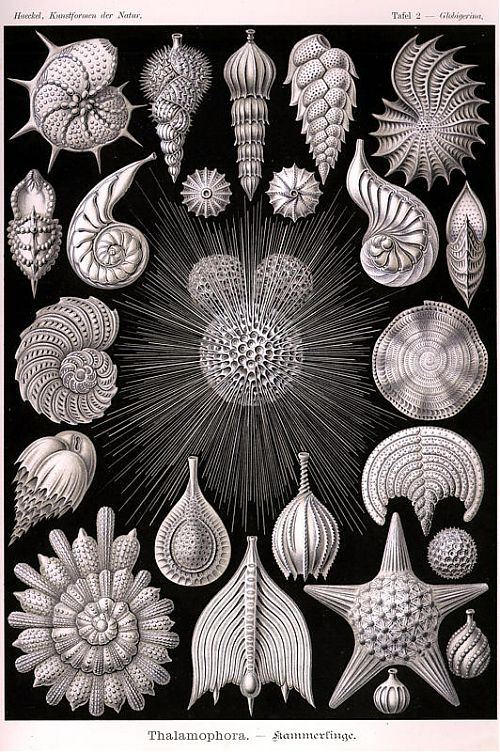

All of this is just the last chapter of Death and Life of Great American Cities all over again. That’s the chapter where Jane Jacobs describes the kind of problem a city is, and suggests that human knowledge needs new tools to understand organized complexity. The longer I live after reading that book, the more I can’t believe how many people haven’t read it, or how I hadn’t heard of it until I was 25. I come back to that book all the time, and it wasn’t even the first thing I read about complexity or emergent systems.

I think the reason Death and Life had such an impact on me might be because Jane Jacobs is so definite and concrete in that book— she really captures the “aha” of suddenly seeing patterns in chaos, of seeing the bigger, realer simplicity. She sums up the problem of cities in only four principles. Four!

The books I’d read before were much looser. Christopher Alexander’s pattern language for designing houses and cities has over 200 items. Godel, Escher, Bach never intends to sum up intelligence in a set of patterns, although it nearly does anyway. Jane Jacobs got her perspective down to a tight, efficient package, without simplifying anything. It’s inspiring.

There are more general introductions to complexity and emergence (like say, Emergence), but I would still recommend Death and Life as the essential tome on the subject. So far. I’m still learning.